Before we dive into more outlining rules, I wanted to address a couple house-keeping notes.

One is that my micro-fiction, Do Wasps Sting When It’s Raining?, will be published in the print version of After Happy Hour Review. Once I get more details, I’ll update the blog. If you’ve ever wanted to own a printed copy of my work, that’ll be the time!

Another item to mention is that I am going to be shifting my schedule of blog updates to be bi-weekly (meaning every other week) rather than the previous weekly. There are a couple reasons for this, but mostly I think it’ll just be easier for me as my work schedule becomes more hectic, my partner and I begin to plan our wedding, and I continue to work on my health problems. Thanks again for patience as I continue to figure out what space this blog takes up in my life.

My second tool in the outlining toolbox that I first discussed two weeks ago is the Pixar storytelling rules, which expand on and reinforce the South Park rules. I’m not going to go through all of them, especially because not all of them are relevant to outlining, but number four is: “Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.”

Keen eyed readers will notice that this rule is very similar to the previous, South Park, rules. There’s a big reason for that: these two items together are the secret. This rule is so important that reinforcing it is the most important thing I can do, and the Pixar rules crystalize this structure so you can lay it on top of your stories.

This rule of each beat affecting and influencing the one after it is at the core of every good story. You can trace it back to Joseph Campbell’s ideas on storytelling shown in his book ‘Hero with a Thousand Faces’, you can see it in Dan Harmon’s story circle. And, most importantly, you can see it your own various movies, books, episodes of TV, comic routines, whatever.

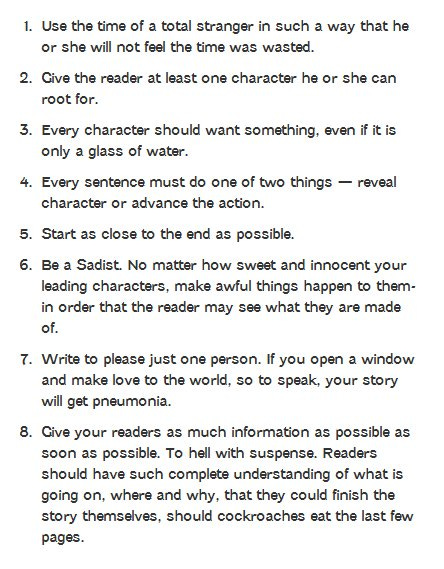

There are a couple of modifications on these rules. The first occurs within the first sentence: change it so that it reads “Once upon a time, there was a ____ who wanted ____.” This comes from Kurt Vonnegut’s rules for writing: Every character should want something, even if it is just a glass of water.

There are other parts of the Vonnegut rules that I will talk about probably in future blog posts, but this is the only one that directly affects outlining.1

This second half of the sentence, where you specify the want of your main character, lets you know who your character is, and helps you understand where they are coming from. It gives you a touch stone to always come back to; if you’re ever lost, you can always look at your protagonist and says, ‘This is a person who wants ____’.

An important note on the idea of “wanting”: want is not the same as need and isn’t always what gets fulfilled by the end of the story. You’ll notice this in the WALL-E outline that the story doesn’t end with WALL-E just being with the person loves. What WALL-E may want at the beginning is to be in love, but what he needs is to not be alone (which is how the story ends).

Another modification that I frequently make is changing the adverb in the “because of that” clause to be more specific to the story. In general, the closer you can make that clause to follow the South Park rules (i.e. allowing you to introduce complications and logical causation), the easier time you are going to have to figure out what comes next. If things are going too easily for your characters, it’s generally a good time for you to throw a wrench in the plans and, if you’ve been reading enough and filling the well, you’ll be able to see where you should go next.

The final modification that I make is providing multiple “One day” clauses. In traditional storytelling, this “one day” is also called the inciting incident, but I believe there can be multiple inciting incidents and they can frequently interact and inform each other.2 Be careful with this as not everything is an inciting incident, but if two things happen on different days and inform each other, you should probably include both of them in your outline.

Reading back this post, there seems to be a lot of rules, so I’m going to try to sum them up here:

Start your outline with “Once upon a time, there was a <description of your character> who wants <their main motivation>.”

Next, establish their daily life. (“Every day, they <blank>.”)

Then, establish the inciting incident(s). (“One day, <blank happens>.”)

Create the beats of your story. Use adverbs such as “but” or “however” to introduce complications, or to have logical causations as a result of the previous beat.

At the end of your story, show the character addressing their need. (“Until finally, <the need is addressed>.”)

Now, let’s take these rules and its modifications and apply it to the WALL-E outline I talked about two weeks ago:

Once upon a time, there was a little robot who wants to fall in love.3

Every day, he sorts through a garbage pile.

One day, he finds a green plant.

One day, another robot falls from space.4

Because he is so alone, he falls in love with the other robot.

Because he is in love, he shows her the green plant.

But then, she flies away because she is searching for the green plant to discover if earth is habitable.5

Because the first robot is in love, the first robot follows the second robot to where all the humans went.

But then, there is an evil robot who wants to keep humans complacent and on the ship.

However, the little robot shares the green plant with the humans.

Because he shares the plant, the humans want to go back home

Because they need to control the ship to go back home, they disable the evil robot.

Until finally, everyone arrive back at Earth.6

Now, for the classic ZK contradiction: these sorts of goal posts, or touchstones can be useful, but don’t let them stifle you. I’ve mentioned many “rules” in this blog, but there really is only one rule in writing: If it works, it works. That’s it. One of my favorite things about writing is when a character surprises you by taking an action that you know is right for them to take, but you don’t know why yet. For me, this usually ends up in multiple pages of me trying to understand where this character comes from, what memories they were using to make that decision, and so on.

The final thing I will mention about outlines, is to only do it when you’re halfway through the first draft. This is not to say that you don’t have an idea of where you are going to go. Having a book that is a “model” for your book, which shows you the types of scenes that could come up, the types of twists you could take, can be very useful. But at your base level, you need to have what Auntie Anne Lamott calls “the child’s draft”; the draft where you let it all out.

Your first draft is the one where you find out what your story is about. The second draft is the one where you make the story fit better the meaning you discovered in the first. It’s only after you truly discover the meaning, that you can figure out what scenes are necessary and which ones to cut.

I am a software engineer by training more than anything else, and we have a saying when working on code that I think applies perfectly to storytelling: “Do it. Do it better. Do it faster.” Outlines are a tool that can help you to do it better.

In two weeks, I’m going to share some examples of media that I’ve outlined: some that work and some that don’t. My recommendation for an exercise is to take one of your favorite pieces of media and outline it, following the above rules. Once you start to look at media this way, you’ll begin to see the outline everywhere, and, hopefully, you’ll start to see it in your own work.

Except for arguably start as close to the end as possible, but I digress.

You’ll see how this works more specifically within the WALL-E outline with the inciting incident of discovering the plant, interacting with the other inciting incident of EVE arriving on Earth.

What he wants is to fall in love, but what he needs is to not be alone (as shown by his interaction with the cricket).

The first inciting incident then informs the second inciting incident, as it allows other things to happen later.

See, we are introducing complications! If the two robots just stayed together and nothing happened, that wouldn’t be a story.

And both WALL-E’s want (to be in love) and need (to not be alone) is fulfilled.